SAN MARTIN JILOTEPEQUE, Guatemala — Migrant, The last Ana Marina López heard from her husband, the 51-year-old Guatemalan migrant informed his family that Mexican immigration agents were detaining him at the United States-Mexico border.

That was two days before a fire in an immigration detention center in Ciudad Juárez killed at least 39 migrants and wounded more than a dozen others.

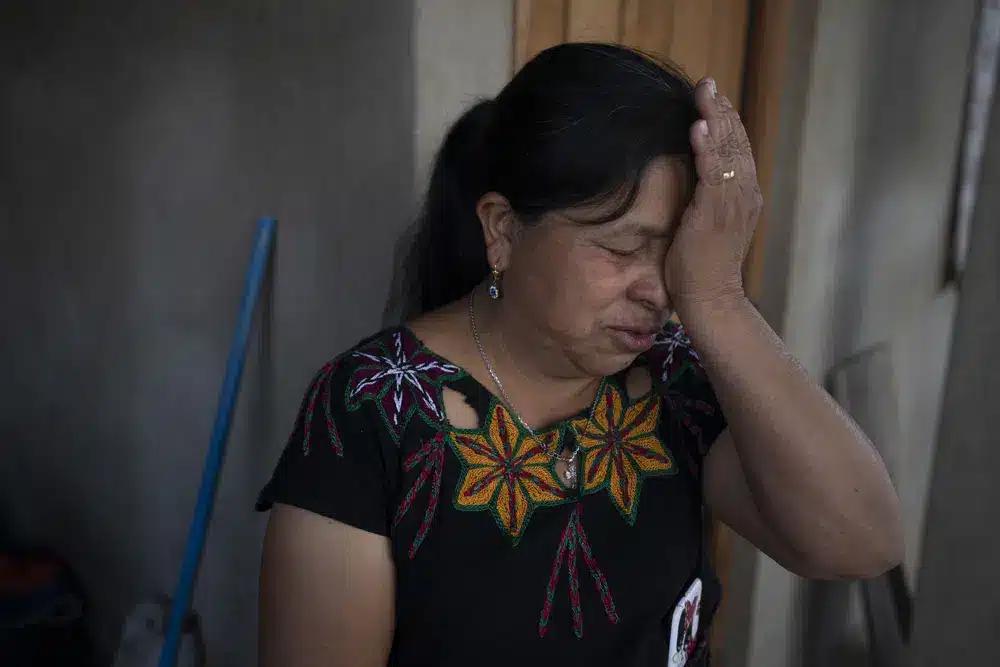

Then his name surfaced on a government list of fire victims, but there was no indication whether he was among the deceased or hospitalized. López and her daughter are now back in their small western Guatemalan town, clinging to the faith that he is still alive.

They’re not the only ones.

Families across the Americas are in agony as they anticipate news of their loved ones as images of the devastating fire flood news broadcasts and social media. Families’ pain and uncertainty highlight how the effects of migration extend far beyond the individuals who start on the perilous journey north, affecting the lives of people all over the region.

Families across the Americas are in agony.

A sister in Juarez, Mexico, awaits word on her Venezuelan brother, who has been anesthetized and intubated in a hospital. Families in Honduras are shocked after watching footage of guards fleeing a growing cloud of flames and smoke in an immigration detention center.

López holds a photograph of her husband in a cowboy hat in Guatemala, unsure whether he is living or dead.

“This should not be possible. “(Migrants) are people; they are humans,” López said, shaking her head. “All I want is justice.” They are not animals and therefore cannot be handled as such.”

The cause of Monday night’s fire is unknown, and authorities are looking into eight individuals, including a migrant, who may have started it.

When López’s husband, Bacilio Sutuj Saravia, left for Mexico in mid-March, he informed her he was going for tourism. Sutuj, who operated a small transport company with two pickup trucks, waited until he was in Mexico to inform her he was going to the United States to see their daughter and two boys.

However, he was never given the opportunity. As he stepped off a bus at Juárez’s station on Saturday, immigration officials detained him.

López found out about the fire from television news coverage. Sutuj’s children had been unable to contact him since he made a brief phone call reporting he had been apprehended on Saturday.

“The authorities should be watching and caring for them, not fleeing and locking them up and burning them.” That bothers me,” López said.

This should not be possible. “(Migrants) are people”

The three families horrified by the surveillance footage are waiting for word on the fates of their boys in the rolling coffee-dotted mountains of western Honduras. The three companions had set out from their small town of Protection for the United States. Like many others in the rural region, the men intended to work and send money home to support their families.

They encountered a migrant smuggler in San Pedro Sula, a major departure point in northern Honduras, who transported them to Mexico.

On Tuesday, three men — Dickson Aron Cordova, Edin Josue Umaa, and Jes Adony Alvarado — appeared on the government’s list of victims without indicating whether they were still living.

“You want to be strong, but these are difficult blows.” “They’re unbearable,” said Cordova’s father, José Córdova Ramos. “We’re waiting for real news, the first and last, as they say, whether they’re alive or dead.”

Their rage mirrors their worry as they watch guards flee as flames and thickening smoke engulf migrants.

Another father starts asking inquiries like, “Who started the fire?” How did they get the flames inside? Did a guard hand someone inside a lighter?

The officers, according to José Cordova, “didn’t want to do anything.”

Stefany Arango Morillo, a 25-year-old Venezuelan nursing student, was left with the same pit in her gut in Ciudad Juarez, near the US-Mexico border.

She and her brother Stefan Arango Morillo, both single parents, fled their northern Venezuelan city of Maracaibo in February, leaving behind three small children between them and their mother, hoping to seek asylum in the United States.

The siblings crossed seven nations in a month to reach migrant Ciudad Juárez.

The siblings crossed seven nations in a month to reach migrant Ciudad Juárez, joining a rising tide of Venezuelans heading to the US border.

Every day, they tried unsuccessfully to register for an appointment to file for asylum in the United States using a smartphone app.

But their journey ended on Monday when Mexican immigration officials detained Stefan and put them behind bars in a detention center that would later burn down.

Stefany desperately searched for her 32-year-old brother, fearing the worst when she got a text message from his phone inside a private hospital. He was still living, but his injuries from smoke inhalation made it difficult for him to speak.

Stefan’s health worsened in the hospital, and the aspiring physical education teacher was transferred to the hospital emergency room in a coughing fit.

Hours later, his sister forced her way into the crowded hospital, kissing her brother’s brow just before he was sedated and intubated.

“He’s playful but also determined,” she said.

She sobs in the hospital waiting area, calling migrant relatives in Venezuela to deliver the news. But, while she waits, she holds out optimism that she will be able to bring him back home.

“It’s like a life lesson,” Stefany explained. “And believe me, I know and have faith that my brother will get out of there and fight for our dream.”

SOURCE – (AP)

___