Brian Johnson was a roof fitter in northeast England before tearing the roofs off arenas as the lead singer of the hard rock phenomenon AC/DC. The “Hells Bells” singer recalls his journey to becoming one of the world’s most acclaimed rock stars in his new memoir.

It’s the classic Cinderella story. Only Johnson, now 75, has been a Cinderella at least three times, never abandoning his goal of singing in a rock ‘n’ roll band.

“I don’t know what it is, but I just never, ever sort of gave in,” he said recently over the phone from his Florida home. “I was always willing to take a chance on something when more pessimistic folks wouldn’t.” “I’ve always seen the glass as half-full.”

“The Lives of Brian Johnson,” published by Dey Street Books, chronicles his ups and downs growing up near Newcastle, culminating with his joining AC/DC and releasing the famous “Back in Black” album.

“The book wasn’t so much to validate my life,” he remarked. “It was to validate the lives of all the beautiful people I met who helped form my life – school friends, factory friends, music friends.”

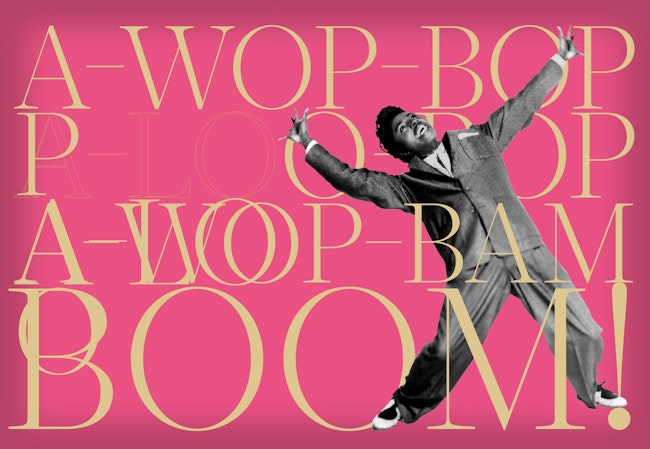

Music was his North Star, and he recalls being 11 years old and freaking out when he first heard Little Richard sing “Awop bop/a-loo bop/awop bam boom.” “Many have described that song, ‘Tutti Frutti,’ as the sound of rock ‘n’ roll being born — which is appropriate because my goal of being a vocalist was also formed at that moment,” he writes.

Johnson was a young father and husband as well as an apprentice engineer. He joined a British Army airborne infantry regiment to acquire enough money for a PA system.

He saw Jimi Hendriks perform when he was 15, and Sting perform when he was 15 and became friends with musicians of Slade and Thin Lizzy. He’d meet Chuck Berry, but things didn’t go well. He writes, “Never meet your heroes.”

Johnson, who would later create the immortal words “Forget the hearse/’cause I’ll never die,” made his stage debut in the delectably named The Toasty Folk Trio, survived a tragic car accident, and eventually found fame with the band Geordie.

The band made it to “Top of the Pops,” which was a huge accomplishment for any new band. He gave up a nice career at his engineering firm, but Geordie only had one Top 10 hit and quickly faded away.

“I’d lost everything at the age of 28.” “Marriage, profession, and home,” he writes. He moved home with his parents and remembered seeing AC/DC on BBC. “I enjoyed every minute of it.” But it was also a reminder that I’d had my chance and wasted it.”

Johnson rebuilt his life, first as a windscreen fitter and then as a vehicle roof repairer, and formed Georgie II. He was overjoyed. He had a small business and a small band. “I believed it was my second Cinderella story,” he adds, “but there was more to come.”

The book explains where his signature headgear came from: He once rushed to a show without changing, sweating glue and glass shards into his eyes. His brother, Maurice, loaned him his cloth driving cap for protection, which the spectators appreciated.

Even still, a part of Johnson remained unfulfilled. A chance meeting with vocalist Roger Daltrey proved decisive. The Who’s leader welcomed Johnson, living with his band in a flat with only four beds on the floor, to his manor house for lunch.

On that day, Johnson recalls Daltrey approaching him bare-chested and barefoot, gripping onto the mane of his galloping white horse (“If this isn’t a rock star, I don’t know what is,” he writes.)

“‘I’m going to give you one bit of advice, Brian,’ he said. Never, ever quit. Do you get what I’m saying? Never, ever, ever lose up.’ “And I took that to heart,” Johnson said. “He probably forgot he said that, but I don’t.”

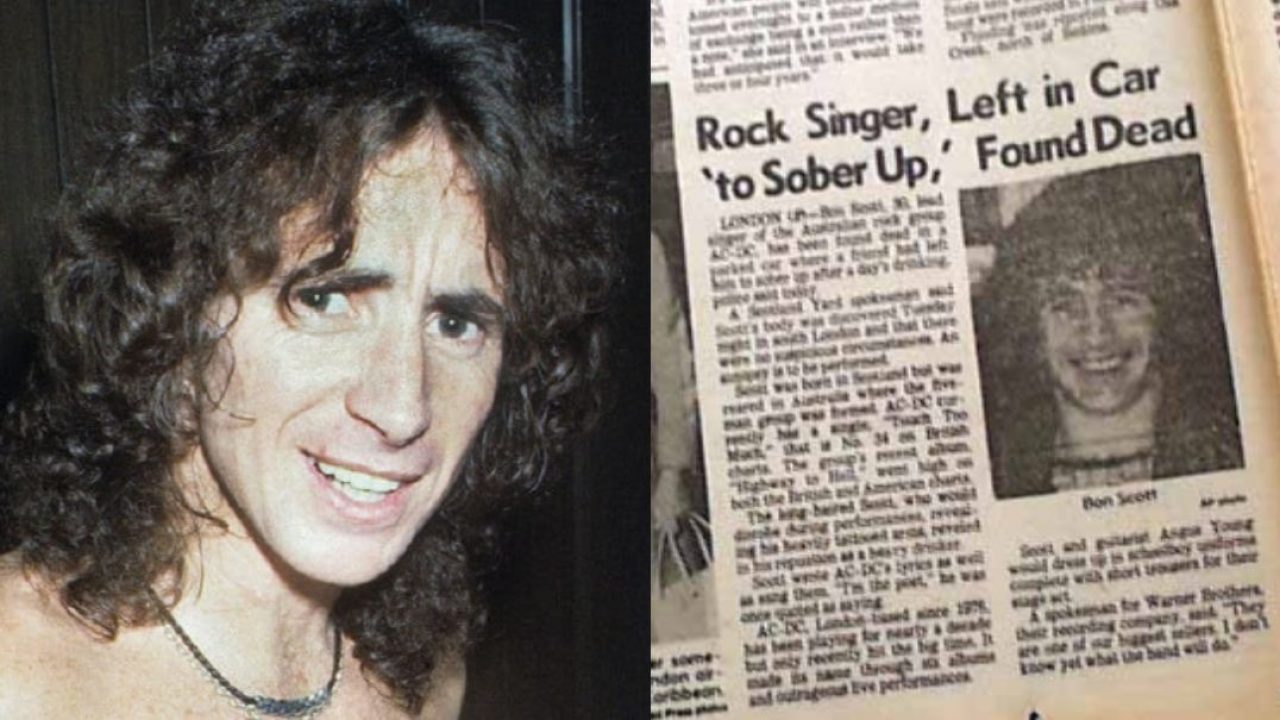

Bon Scott, AC/original DC’s lead singer, died in 1980, and Johnson was given an audition to replace him based on recommendations, including one from Scott himself, who had heard him perform one night. Johnson didn’t realize they’d met until years later.

Malcolm Young, co-founder and rhythm guitarist, offered Johnson a Newcastle Brown Ale during the audition, a charming tribute to Johnson’s ancestry. Johnson’s first song with the band at the audition was Tina Turner’s “Nutbush City Limits.” (“It was the most electrifying experience of my life,” he writes.) They then performed some AC/DC songs. Of course, he got the job.

Rowland White, the author of “Into the Black,” Johnson’s editor, said the shape of Johnson’s story is “exceptional because it doesn’t normally happen like that.”

“He was content that he’d given it a shot and made peace with it.” And it makes the shot at AC/DC feel more pleasant since it’s no longer something he’s strained for.”

The book concludes just as Johnson fulfills his lifelong dream. If fans want to know more about AC/beginnings, DC, he says, that’s not his narrative to tell – that’s for surviving members guitarist Angus Young, bassist Cliff Williams, and drummer Phil Rudd.

“That book belongs to the people who were there from the beginning,” he continued, “because that’s what I want to hear.”

Johnson is a natural storyteller, and his manager was the one who recommended a memoir. Johnson fought back. “Every week, some aging actor or musician publishes a book.” ‘No, not another one,’ I’ve always said.

Johnson, though, was urged to write a few chapters and sat down with a yellow legal pad. He wrote a book a few years later, which he dedicated to his great-great-great grandkids.

Why? On the way to his grandfather’s funeral, he asked his father about him. His father described him as “just a dude.” Then he inquired about his father’s grandfather, whose response was, “How the hell would I know?”

“I thought to myself, ‘What a shame, what a pity,'” Johnson added. “A few generations later, no one knows anyone.” As a result, I composed it for my grandchildren. I hope this book’s writings will help you get to know me a little better. And I hope you have a little piece of me in you and that you have a long and happy life.”