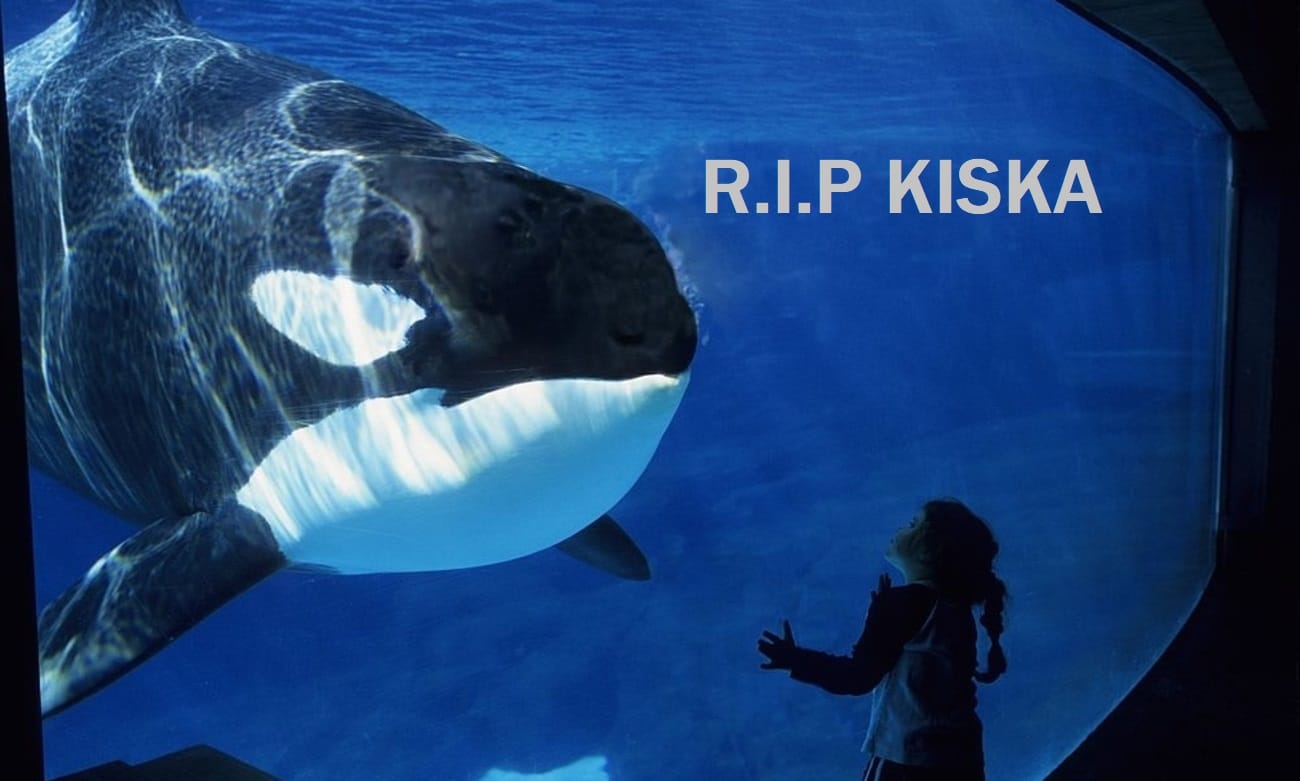

The Ontario government said that Kiska, Canada’s last captive killer whale, died late Friday, adding that the theme park where Kiska lived informed them of her death. MarineLand informed the ministry that the whale named Kiska died on March 9, 2023.

MarineLand has hired professionals to perform an autopsy. “In an emailed statement, Brent Ross, a spokesperson for the Canadian province’s solicitor general ministry, said.

MarineLand is a Niagara Falls, Ontario, theme park. Kiska was apprehended in Icelandic waters in 1979 and was about 47 years old at the time.

Kiska’s health had deteriorated in recent weeks, according to MarineLand.

“Marine mammal care team and experts did everything possible to support Kiska’s comfort and will mourn her loss,” the theme park said, according to local media.

Animal Justice, a Canadian non-profit organization that advocates for animal rights, has called for an investigation into MarineLand’s treatment of the killer whale.

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) described Kiska as the “world’s loneliest Orca whale,” whose life had been marked by “tragedy after tragedy” after all five of her calves died before reaching the age of seven.

“Animal Welfare Services was present to ensure compliance with the Standards of Care,” Ross explained. According to Ross, Marine Land has been inspected 160 times since January 2020 as part of Animal Welfare Services’ efforts to ensure that legal standards of care are met.

Concern Over Killer Whales (Orca) in Canada

According to Nature Canada, Orca Whales, one of the world’s largest animals, is a Dolphin family member (Delphinidae). Males can grow to be ten meters long and weigh 22,000 kilograms. Females are slightly smaller but still substantial, at 8.5 meters long and 7,500 kilograms. These magnificent creatures, highly intelligent and distinguished by their black-and-white coloring, are also lethal.

They are carnivores at the top of the oceanic food chain, with often geographical and population-specific diets. The Killer Whale’s diet could include fish like salmon, herring, and tuna and larger marine life like seals, sea lions, penguins, sharks, and other whales and porpoises.

Orcas are extremely social creatures that live (and hunt) in matriarchal family pods of five to fifty whales and communicate using echolocation. Killer whales can be found worldwide, from the polar ice caps to the tropics near the Equator.

There are populations in Canadian waters in the northern Pacific along British Columbia and, less frequently, in the Atlantic and Arctic. This has begun to change in recent years as sea ice recedes and occurs for shorter periods each year.

One effect of melting and retreating ice and the increasing unpredictability of ice formation schedules is a shift in Killer Whale roaming patterns, as they now venture into far northern waters where they previously did not.

Because of their long dorsal fins, orca whales typically avoid ice. However, with the loss of year-round sea ice in the Arctic, these cetaceans, which were previously largely absent from the region, are now spending more time there and visiting previously inaccessible areas due to permanent or seasonal ice cover.

Killer Whale sightings, which were once uncommon in Hudson Bay, have been reported in the summer and winter.

The Impact of Orcas in the Arctic

Killer whales in the Arctic are also causing havoc on the region’s fragile ecosystem. Narwhal disturbance is one such documented effect. Narwhals, also known as “sea unicorns” due to the prominent tusks seen on males, are shy, wary whales that have been difficult to study due to the remoteness of their chosen habitats—two of three recognized Narwhal populations live in Canadian Arctic waters, with the third in eastern Greenland.

A 2017 study found that the presence of Killer Whales significantly impacts the behavior and distribution of Narwhals. Narwhals will move closer to the shore when Killer Whales are nearby, understandably fearful and distressed by the predator.

Killer Whales, which hunt in packs, will attempt to push Narwhals into deeper waters before encircling their terrified prey. Narwhals become further away from the abundant stocks of fish that they eat by moving to shallower waters to avoid Killer Whales. Furthermore, staying close to the shore makes them more vulnerable to hunters.

Because narwhals are an important food source for the Inuit, introducing killer whales into the Arctic increases competition for scarce food sources. In addition to the Narwhal, Killer Whales prey on Beluga and Bowhead Whales in the Arctic. Killer Whales are poised to become a major Arctic predator as sea ice recedes and climate change continues.

Scientists are still studying Killer Whales and their impact on the Arctic marine environment. Questioning the local Inuit, who directly observe these whales’ daily behaviors and interactions in the Arctic, has proven useful.

Scientists use Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) to help form a clearer picture of orcas in the Arctic by combining firsthand observations and cultural knowledge accumulated over generations with their research.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-595710436-e9fb5588826f403193ff399bcc8c0d3d.jpg)