NAGASAKI – On Ikitsuki Island, tucked away in rural Nagasaki Prefecture, a handful of believers meet quietly in a small room, barely bigger than a tatami mat. Here, they worship their “Closet God,” surrounded by scrolls and paintings that keep their faith disguised.

One painting shows a woman in a kimono, styled like a Buddhist figure but meant to represent Mary holding Jesus. Another features a man with camellias, a hint at John the Baptist’s story. These sacred items, once hidden for safety, are reminders of a time when being Christian in Japan came with great risk. Now, the Hidden Christians—known as Kakure Kirishitan—are fading away, leaving behind a story that shaped Japanese religious history.

The roots of Hidden Christianity trace back to the 1500s. Jesuit missionaries, including Francis Xavier, reached Japanese shores in 1549. Their teachings spread quickly in Kyushu, especially around Nagasaki, where trade brought new ideas.

Both local leaders and common folk converted in large numbers. Daimyo such as Ōmura Sumitada welcomed foreign traders, helping Christianity flourish. By the late 16th century, places like Nagasaki, Ikitsuki, and the Gotō Islands were dotted with churches and seminaries.

But in 1614, the Tokugawa shogunate banned Christianity, fearing it might weaken their grip on power. Missionaries were forced out, and followers faced harsh punishment. Authorities used tactics like fumi-e, making people step on images of Jesus or Mary to show they had abandoned the faith.

Those who refused suffered torture, crucifixion, or exile. In the 1620s on Nakaenoshima, near Ikitsuki, many Christians were killed, and relics from that time, like a holy water bottle, are honoured to this day.

Christians went into hiding

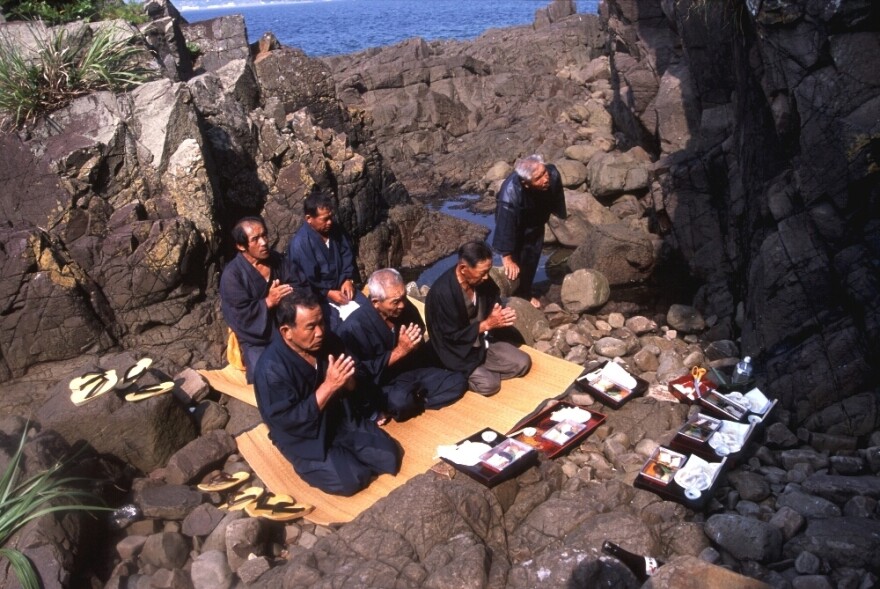

To stay safe, Christians went into hiding. They moved to remote islands like Ikitsuki, Gotō, and Kuroshima, blending their rituals with Buddhist and Shinto practices. Prayers in old Latin, passed down by memory, became a part of family life. Sacred items like scrolls and rosaries were hidden in secret rooms. Only trusted community leaders, called Chokata or Mizukata, led ceremonies. This hidden faith survived more than two centuries through strong community ties and secrecy.

Everything changed in 1865, when Hidden Christians from Urakami, led by Sugimoto Yuri, revealed their faith to Father Bernard Petitjean at Ōura Cathedral. This moment, later called the “Miracle of the Orient,” surprised the Catholic Church.

It showed that Christianity had survived Japan’s long years of isolation. When Japan lifted the ban on Christianity in 1873, many Hidden Christians joined the Catholic Church, but some chose to keep their traditions, staying loyal to their ancestors’ ways.

On Ikitsuki, these customs lived on, but now they’re at risk of disappearing for good. In the 1940s, the island had close to 10,000 Hidden Christians. Today, local estimates put the number under 100. The last known baptism took place in 1994, a clear sign of decline.

Masatsugu Tanimoto, a 68-year-old farmer, is one of the few left. “It’s sad to think we might be the last ones,” he says. Tanimoto leads Latin Orasho prayers at the Ikitsuki Island Museum, but he is among the youngest of the remaining followers—most are now elderly.

Hidden Christians survived

Several social changes have sped up this decline. Hidden Christianity survived because small villages supported close-knit rituals. But after World War II, Japan’s rapid modernization broke up these communities. Young people moved to cities.

Women, who once kept household traditions alive, started working outside the home. “Individualism makes it hard to sustain Hidden Christianity,” says Shigeo Nakazono, who runs a local folklore museum and has studied the group for three decades.

Orasho prayers, once the heart of the faith, are now heard only a few times a year, often in the museum rather than private homes. Nakazono has recorded hundreds of videos of these rituals since 1995, hoping to save what’s left. But younger people show little interest. Tanimoto admits, “Nobody wanted to carry it on.”

The importance of Hidden Christians reaches beyond Ikitsuki. In 2018, UNESCO recognized 12 sites in Nagasaki and Amakusa as World Heritage sites. These include villages and old churches, such as the Former Gorin Church and Rōya no Sako Martyr Memorial Church, standing as reminders of the faith’s long struggle. While tourists visit these places, it hasn’t stopped the population from shrinking.

For Masashi Funabara, a retired city hall worker and Hidden Christian, the faith is more than religion. “It’s our history, our identity,” he explains at the Shima no Yakata Museum. The Kakure Kirishitan shaped a unique theology, separate from Catholicism, forged by years of isolation. Many feel that joining the Catholic Church means forgetting the sacrifices made by their ancestors.

As evening falls over Ikitsuki’s rice terraces, the Orasho prayers echo softly, a fading memory of a faith that once stood strong despite danger. The story of the Hidden Christians is one of courage and dedication. But with so few left, their prayers may soon become history.

“The Kakure Kirishitan faith could vanish one day,” Nakazono says. “I need to record its traditions so others can learn from them.” For now, the Closet God remains, quietly kept in the hearts of the few who still remember.