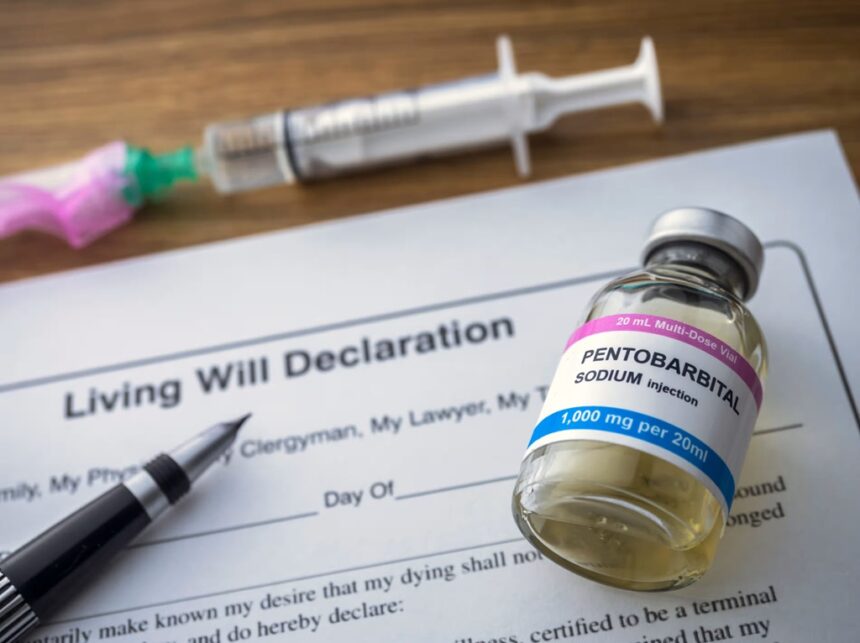

Canada has seen a sharp increase in medical assistance in dying (MAID) since its legalisation in 2016. The number of assisted deaths rose from just over a thousand in the first year to more than 15,300 in 2023.

That accounts for 4.7% of all deaths in the country, up from 4.1% in 2022. Annual growth rates have averaged 31% in recent years, though 2023 showed the first signs of slower expansion.

This rapid growth has become a focal point of debate within Canada and abroad. Discussions range from the program’s original focus on terminal illness to new and controversial expansions, including requests from those with mental health conditions or people in precarious social circumstances.

Provincial differences have also emerged, with Quebec and British Columbia reporting the highest rates. As public support stays high, around three-quarters nationally, the program’s direction raises questions about sustainability, provider capacity, and safeguards. The ongoing debate underscores a turning point for end-of-life care and the values shaping Canadian society.

How MAID Became a Major Force in End-of-Life Care

Canada’s approach to assisted dying has changed dramatically in less than a decade. Policy updates, court rulings, and growing public acceptance have pushed MAID from a controversial new measure to a routine option for thousands each year. Reviewing its legal changes and demographic reach shows just how quickly assisted dying has become a defining feature of end-of-life care in the country.

Timeline and Legal Milestones in MAID Expansion

The story of MAID’s rise begins with a shift in national law. In June 2016, Parliament legalised medical assistance in dying for adults with serious illness facing a “reasonably foreseeable” natural death. This move placed Canada among a small group of countries with broad assisted dying access (Canada’s medical assistance in dying law).

The framework evolved. In 2021, Bill C-7 brought major updates, prompted by court decisions and advocacy efforts. Changes included:

- Easing the requirement that death be “reasonably foreseeable.”

- Adding safeguards for people whose deaths were not imminent, including a 90-day assessment period.

- Excluding those whose only medical condition was mental illness (pending further review).

This update widened eligibility and signalled a move beyond terminal illness alone (Medical assistance in dying: Legislation in Canada). The new rules responded to feedback from patients, families, and the courts, and triggered a jump in the number of applications.

By 2023, the requirement for a foreseeable death became less central, opening the door for more people with chronic or serious conditions, but not facing imminent death, to apply for MAID (Get the facts on MAID). Policy changes have made Canada’s program one of the most accessible in the world.

Statistical Snapshot: Record Numbers and National Impact

Recent counts underline the speed and scale of the shift. In 2023, more than 15,300 Canadians chose MAID, making up 4.7% of all reported deaths—a greater share than in previous years and a sharp climb from just over 1,000 cases in the first full year of data (Medically-assisted dying in Canada reached record high). For comparison, no European country with assisted dying laws sees such a high proportion of deaths due to assisted dying each year.

A closer look at Health Canada’s report reveals:

- MAID deaths have grown by double-digit percentages annually since 2016.

- Increases appeared to slow in 2023, yet the share of MAID deaths remains unprecedented for a G7 nation.

- Nearly 1 in 20 Canadian deaths now involve medical assistance in dying.

This rapid uptick is unique among countries with similar laws. Advocates say the change shows high demand and effective access; critics cite concerns about safeguard erosion and the risk of MAID being used for reasons beyond terminal illness (Fifth Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying).

Regional and Demographic Patterns

Patterns vary across the country. Regional data shows Quebec and British Columbia consistently have the highest rates of MAID. Quebec’s established hospice networks, social attitudes, and legal clarity have helped normalise the practice. British Columbia follows closely, with streamlined processes and robust palliative care services.

Other provinces, especially those with more rural populations or complex access procedures, report lower MAID uptake. Provincial health policy, local provider willingness, and public awareness each play a role.

The typical recipient profile, according to federal data, is:

- Between 65 and 85 years old.

- Living with cancer, followed by heart or neurological disease.

- Residing in urban areas, which have both more requests and more providers (Fourth annual report on Medical Assistance in Dying).

Urban patients are more likely to receive MAID, reflecting differences in health system capacity, physician participation, and patient resources. Gaps persist in some rural areas, where fewer healthcare professionals are available to perform assessments or provide the service.

As a result, while access is broad, differences in provincial health systems and demographics shape who receives MAID and when. The ongoing changes in policy and medical infrastructure suggest these patterns will keep shifting as the program matures.

What is Driving Canada’s Rapid Increase in MAID?

Canada’s sharp rise in medical assistance in dying (MAID) cases is not due to a single factor. It reflects broad shifts in policy, increases in provider capacity, heightened public awareness, and ongoing differences among provinces. At the same time, a changing patient profile and wider discussion about ethical safeguards shape the decision-making landscape. This section examines the main drivers fueling the rapid growth in MAID.

Policy and Healthcare System Factors

A series of policy changes have expanded both eligibility and access to MAID in recent years. Major legal updates in 2021 widened the range of people who qualify, no longer requiring a “reasonably foreseeable death” for most applicants. This expansion opened the door for people with chronic illness, not just those with terminal conditions, to access MAID.

Several factors in the health system push this trend forward:

- Expanded Provider Networks: More doctors, nurse practitioners, and care teams are now authorised and willing to provide MAID, strengthening the system’s ability to meet demand.

- Increased Public Awareness: Widespread media coverage and government outreach have made the rules, application process, and rights around MAID easier to understand for the public (Canada’s medical assistance in dying law).

- Provincial Differences: Each province has flexibility within the federal guidelines, creating local pathways that either speed or slow access (Medical assistance in dying: Overview). Quebec leads with robust infrastructure, while rural areas sometimes lag due to fewer providers.

- Consistent Data and Reporting: Laws now require clearer data collection, which helps policymakers track trends and make targeted improvements.

These changes have normalised MAID within routine medical care. Disparities remain between urban and rural areas, but overall, more people can access MAID than ever before (Canada’s assisted dying laws in spotlight as expansion …).

Patient Demographics, Diagnosis, and Social Determinants

The typical Canadian MAID recipient is between 65 and 85 years old, living with cancer or an advanced neurological or cardiac condition. Most recipients live in urban centres, notably in Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia (Fourth annual report on Medical Assistance in Dying …). Several factors shape who accesses this option:

- Age and Diagnosis: Older adults, especially those with cancer, drive the largest share of MAID requests. Non-cancer illnesses—including heart failure and neurodegenerative diseases—are increasingly represented.

- Nature of Suffering: According to national reports, about 96% cite loss of ability to engage in meaningful activities or daily care as key reasons for choosing MAID (Nature of Suffering People Who Received MAID Canada).

- Social Factors: Access to healthcare, support networks, literacy about end-of-life choices, and geography all matter. Urban dwellers benefit from denser provider networks and better information, while those in rural areas may face barriers due to distance or limited health resources.

- Ethnicity and Culture: Most MAID recipients are identified in reports as Caucasian, with much smaller uptake in other ethnic groups (Medically-assisted dying in Canada reached record high …). Cultural norms and language barriers may affect choices, but research is ongoing.

These demographic trends are shaped not just by personal health but also by underlying inequities in access, education, and social support. The data show that MAID is most often accessed by those with the means and knowledge to navigate Canada’s health system.

Debate: Autonomy, Vulnerability, and Safeguards

A critical part of the conversation centres on autonomy versus the risk of harm to vulnerable people. Supporters of MAID stress the right to self-determination for the ill and dying. They argue that current rules respect patient choice and dignity.

Others worry about unintended consequences:

- Safeguard Strength: With broader eligibility, some believe existing safeguards may not be enough to protect those who are isolated, struggling with mental illness, or economically disadvantaged.

- Provider Concerns: Some healthcare professionals have raised conscientious objections, citing ethical, moral, or religious grounds (Ethical arguments against coercing provider participation in MAID).

- Risk of Expansion: Critics point out that as access grows, so does the risk that MAID could be offered in cases where suffering is linked to poverty, loneliness, or lack of care, rather than to incurable illness or pain (Medical Aid in Dying: Ethical and Practical Issues – PMC).

- Balancing Rights and Duties: The country continues to review and update legislation to manage risk and maintain trust among the public, providers, and patients.

Canada’s debate is ongoing and reflects tensions present in other countries. The balancing act between respecting patient wishes and guarding against abuse or error shapes every major update to the law (Have Arguments For and Against Medical Aid in Dying Stood …).

These factors together help explain why Canada’s MAID program is expanding so quickly, why it is more widely accessed than in other nations, and why its evolution remains a subject of close public, political, and ethical scrutiny.

The Future of MAID: Stabilisation or Continued Expansion?

Canada’s medical assistance in dying (MAID) program is at a crucial point. After years of rapid growth, new data signals a slowing pace. Legal changes and public debate are now focused on the extent of MAID’s future reach. This section breaks down signs of stabilisation, policy debates on who can access MAID, and how Canadian trends compare abroad.

Slowed Growth: Are We Hitting a Plateau?

Federal reports from 2023 show over 15,000 people received MAID, but for the first time, the annual growth rate slowed. While overall numbers reached new highs, the increase year-over-year was much lower than in previous years.

- Data from Health Canada reveals that after several years of 30%+ growth, 2023 brought a marked reduction in the rate of increase.

- Analysts point to factors such as:

- Most eligible patients have already accessed the program.

- Some provinces may be reaching a natural limit based on population and provider supply.

- The vast majority—96%—of assisted deaths still involve people with terminal conditions (CBC report on slowing MAID growth).

Quebec and British Columbia continue to report the highest rates, while some provinces are slowing. Experts suggest this could mark a plateau, but ongoing policy changes may influence future numbers (Medical assistance in dying up in Canada, but growth has slowed).

Policy Debates on Expanding Eligibility

Policy discussion is now focused on two main fronts: advanced requests for conditions like dementia, and the looming expansion of mental illness as a sole qualifying condition.

- Advance requests would allow people diagnosed with conditions such as Alzheimer’s to choose MAID in the future, even after losing the ability to consent. Quebec has already begun moving in this direction, but opinions are sharply divided. Critics warn of serious risks, including wrongful death and loss of personal autonomy (Policy Brief: The Risks of Advance Requests for Medical Assistance in Dying).

- Parliament recently delayed eligibility for those with mental illness as the only condition until March 2027. Debate continues about how to balance protection for vulnerable people with respect for autonomy. Many providers have called for strong safeguards and more mental health resources before moving ahead (Health Canada on eligibility and delays).

Federal legislation remains under review as expert panels and advocacy groups weigh in. The conversation is now centred on ethical complexity and the risk of expanding eligibility too quickly.

International Influence and Canadian Public Opinion

Canada’s MAID program is now among the most widely accessed worldwide. No other G7 country has a higher ratio of assisted deaths to total deaths.

- In the Netherlands and Belgium, where assisted dying has a longer history, the share of deaths attributed to the practice is lower than Canada’s. Their laws also allow MAID for psychosocial suffering, but uptake rates differ.

- The Canadian public remains broadly supportive. National polls show about three-quarters of Canadians back some form of MAID. Attitudes shift, however, when asked about expansion for mental illness or allowing advance requests for dementia. Many Canadians express unease about stretching eligibility too far.

Ongoing debates in Parliament and civil society are influenced by both local experiences and international examples. Current data and polls suggest Canadians want options but also favour careful control over any further expansions (Canada’s rate of medically assisted deaths rises to record levels).

Canada’s next steps will likely be shaped by these policy questions and the country’s collective judgment on how far to extend one of the world’s most accessible medical assistance in dying programs.

Summary

Canada’s rising MAID numbers signal a fundamental change in how the country approaches end-of-life care. The steady increase—now at nearly 5% of all deaths—reflects growing acceptance, expanded eligibility, and a clear public demand for greater personal choice. Policy changes have made access more straightforward, but they have also sparked ongoing debate about the right balance between autonomy and safeguards.

The current data shows that Canada leads globally in assisted deaths as a share of total mortality, with most people seeking MAID facing serious illnesses, but a small and growing portion now includes those with complex, non-terminal conditions. This trend raises important questions about oversight, support, and health system readiness.

As lawmakers consider further expansions or new restrictions, careful and ongoing review will be essential. Ensuring that protections keep pace with growth and that care remains equitable across regions and groups relies on clear policy and public input. Future updates will watch how both national and provincial practices evolve.

Readers are encouraged to follow developments, discuss perspectives, and share input on this evolving aspect of Canadian society. The impact of MAID will continue to shape personal decisions, medical practice, and the wider conversation about dignity and choice at the end of life.